The Dakotas

Lighter than Air. Featuring iconoclast Alvah Clyde Holmes.

Thank you to Best Made Co., The National Parks Service – Badlands, and others for your support.

Info

Photo Essay By Christina Holmes.

Writing By Justin DenHerder.

Location

Dakotas, United States

2017

“I was taught to strive not because there were any guarantees of success but because the act of striving is in itself the only way to keep faith with life.”

Lighter than Air

By Justin Den Herder

He leaves voicemails but the girls don’t return his calls. He’s not even sure he has their addresses right anymore. There’s a picture thumbtacked to the sheet rock of the sparsely furnished room, the one personal effect they’ve allowed him. He studies it, as he has many times; the three of them crammed into the gondola of the ferris wheel at the state fair, one on each side of him. The wheel had unexpectedly swung into motion, blurring the slightly panicked smiles on the girls faces, the colorful carnival lights are floating orbs on the backdrop of night. Cynthia had taken it. Joy frozen into a five by seven photograph. Outside, snow upon the plains like a great white tablecloth. He thinks about them constantly, the girls, their lives moving on, his presence transitioning to a distant memory. Jack places the photo between the folds of the little pamphlet they’ve given him and tucks it into his flannel pocket. Life is promise and despair. By the time you get to the end of it, the two cancel each other out. Simple philosophies are better and he went all-in on this one, he had to, since he’d had a such a long run of, well, despair. It fuels the tiny engine of hope buried deep in his heart, knowing that promise would have to make a comeback. But he had spent his life working on engines, how long could it— You search within, he repeats to himself. You assign your own value to the days.

…

The storage unit is a coffin for his past. Jack visits it every Sunday morning, as though paying respects. He lifts up the garage door, kicks over an empty handle of Blanton lying on the concrete, scoffs, unfolds the lawn chair that leans against the wall, pulls a cigarette from the breast pocket of his t-shirt, lights up, gulps his black coffee. His shadow is the shadow of a gravedigger on a lunch break, stretching across his rock collection, the love seat draped beneath painter’s cloth, the tool chest, a carburetor wrapped in oil-stained rags, Jenny’s little plastic stegosaurus, a pair of dusty corral boots from Uttech’s. He pulls open the top drawer of the tool chest and goes for the pewter flask. Shakes it. There’s still a taste in there. He unscrews the top and smells the whiskey. Puts it to his lips, then thinks better of it. Disgusted, he throws the flask against the block wall of the unit. He sits back down, head in his hands. The boots are within arms reach. He opens the tin with his polish kit and buffs them until they gleam like they used to.

…

The needle is pushing E and he’s ten miles outside of town. God, how he had loved roaring down this interstate back then, making a beeline for the horizon, windows down, Amarillo by Morning through the speakers, traces of glory across the land. On one side of him, the rising sun kissing the fringes of the mesa, the sandstone walls gone gem-red, on the other side, the eternal, mallet-flattened earth, endless sand and mesquite and all that liquid gold flowing underneath. Oceans of it. The truck bed was loaded up with the bits: tricone-headed, diamond-toothed — at 100-140 rpm they’d decimate the shale, grind it right down to powder. Now his truck bed is empty. The shadows of clouds move over the land. He pulls off at the next exit. The downtown is vacant, wooden planked facades in disrepair, windowsills coated in dust, even the door of the general store is boarded up. The metal Texaco sign at the corner of East River and Main has streaks of rust bleeding from the logo, the red pumps are petrified soldiers long out of service, an unlit neon sign hangs in the convenience store window, the roof partially collapsed, a pillar of sunlight highlights the empty racks. Looking down at the gasometer, he curses his luck and tries to think of the next closest filling station. That’s when he first notices the figure, donning a colorful woolen blanket turned shawl via a scissor-cut hole for his head. He is chanting, his aged face worn like clay after a rainstorm, with strong, sharp native features, his hair still miraculously dark with only a few strands of silver. There’s a paintbrush in his right hand. He looks skyward, waving the brush like a baton, demanding inspiration from the firmament. There are a handful of earth tone paints laid out across the parking lot pavement. Alternating whoops of glee with solemn bouts of silence and concentration, he bends low, makes a flourish with his brush upon the pizza box serving as his palette, then with dripping brush, he jumps up, swipes at the ruins of the convenience store, pauses to observe the significance of each stroke, bends low again with an agility that belied his years, hops around, knees bent like a baseball catcher, swirling here, dotting there. Jack slowly approaches, curious but cautious. The native pauses, stands and looks over, wildly waving him closer. Jack looks astonished at the mural, an intricate landscape with canyons and gorges bathed in a blush of sunset, marvelous in its spectrum of colors, a mysterious and large white cloud, or chariot of some sort, appears to be descending upon the scene. As Jack studies the masonry wall, the native places an old hand upon his shoulder. He points at his work. “Hiinono’ei.” Then puts his finger into Jack’s chest. “Hiinono’ei!” The painter gives a quick nod and repeats the phrase, now placing a hand on each of Jack’s shoulders, smiling fully. What teeth remained in his mouth are outlined with the residue of decades of tobacco. The man’s translucent eyes are like frosted glass. He’s silent, the ancient eyes transmitting a deciphered universal code, entrusting him with it. Jack can't look away from the shaman. A sensation overtakes him, a surge of belonging, of companionship. All other physical senses are obliterated. When he repossesses himself he’s standing alone before the mural. The native is gone, the paints too. He returns to the truck and turns the ignition. The tank is full.

…

He tosses the last of his belongings into the dumpster. Funny, how a lifetime of accumulation disappears in a single hour of purging. Turning back to the unit, he notices the little plastic dinosaur laying on its side on the concrete. He pockets the talisman. He attempts to light up a cigarette but another bout of coughing overtakes him. He spits red, then regains his composure. The spore of age, dormant within him, has released it’s agents. He owns the aches, the weariness, the sickness. But he’s never been one to complain.

…

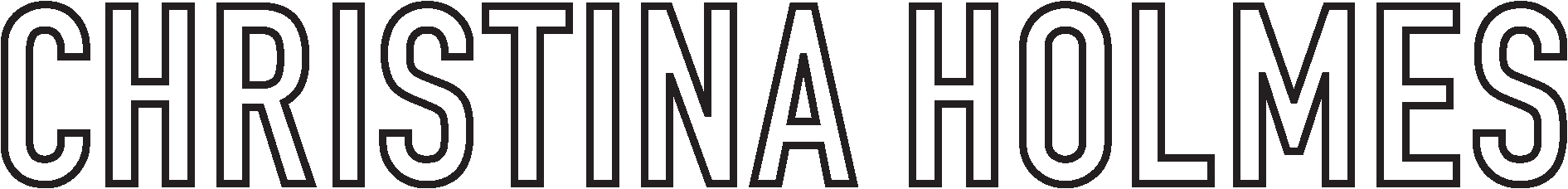

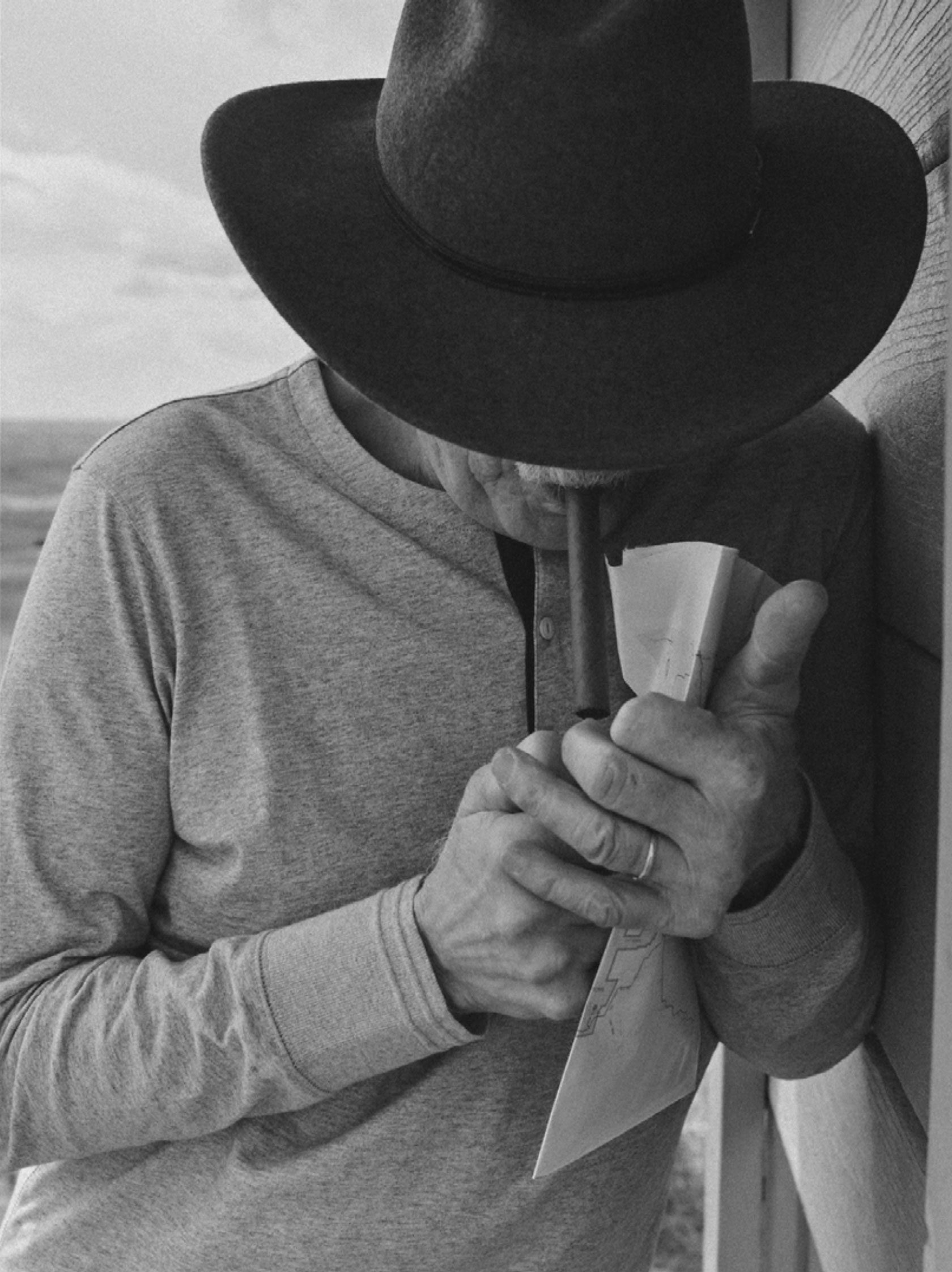

He slugs down the last of his coffee. A few hours north of Bowman, he stops at the National Park entrance and throws on his backpack. Everything that I got, is just what I got on. His gear and camping supplies are carefully compartmentalized and stowed in his pack. He sets off into the stillness of the Badlands; there’s no stirring breeze, no trickling waterfalls, just the calming hand of the land. By late afternoon, using the canyon wall and the branches for balance, he limps his way down into the gorge. The roar of the highway becomes a distant, infrequent whisper. The casual day hikers have become scarce. He follows the bends of the river, slow flowing, the anti-time, his feet sinking into the sandy banks. Taking a cue from the river, he slows to go at his own comfortable, steady pace. By late afternoon, he hasn’t seen another soul for at least a few miles. Three large buzzards circle him in the sky, swirling and ominous. He pauses for a moment, takes some water, pulls out his map of the park to study his progress. He has a few handwritten markings on it, including a red-inked circle marking his destination. His back is drenched in sweat and his bad knee is screaming. He wipes his brow with his sleeve. With the sun bending low, elongating the shadows of the hills, he attempts to pick up his pace, pushing to reach the spot before sundown. He begins ascending out of the gorge. The land is folded, corrugated, furrowed. The layered pigments of the geology reminds him of Abby’s second grade sand-art project, the newspaper spread over the dining room table, a miniature quarry of colored sand piles, her excitement, the brilliant strata of colors that could only be conjured up by the mind of a child,. All that stuffed into a few mason jars. For a moment, the sun is a golden portal to heaven sitting on the horizon. The sky celebrates. He reaches a small, flat outcropping. The land opens up for miles as if spilled from some gargantuan vessel; sweeping, unending, otherworldly. The tops of the hills are brightened only by the last remnants of tangential sunlight. The swarm of dusk is already overtaking the earth. Surely this must be the place. He sets down his pack, bursts into a fit of coughing. When he recovers, he lights up anyway, sending little smoke signals into the approaching night. He lays out his sleeping bag then fixes himself a little meal over a small fire. Eating alone, he looks out over the country reminiscing about the weeks he’d spent out in the oilfields amongst the vastness, the 500 mile days from Bismark to Billings, the non-stop drilling, the thirty hour shifts, the roughnecks and their dreams mingling with the cigarette smoke that collected under the ceiling of the Elk’s Lodge. Back then, if you’d showed him a spoonful of sedimentary he would have the right bit to you within twelve hours. The land surrenders it’s bounty for the sake of transportation, for luxury, for progress… for naught. It knows the end from the beginning. Night descends and the land remembers that it was once an ancient sea bed, the clouds floating by slowly, colossal creatures, their underbellies illuminated with a lunar glow. One by one the heavenly bodies begin to dot the universe. The stars are twinkling like the little prisms of tears that had formed at the corners of Cynthia’s eyes. The earth transforms into a cradle of stillness; the same land that, in his youth, had mocked him with its expansiveness, that had taunted him as though it was something to be trampled, conquered, sucked dry. It suddenly strikes him. He had often witnessed beauty but had never sensed awe. The night air is a cloak of peace draped over his shoulders. His past life, his past transgressions, are jettisoned into the tide of the evening chinook. Release. Free to drift, free to exist as he was, as he is. An overwhelming barrage of warmth ensconces him. Memories, as if projected down from the stars, flood his mind: Cynthia, the girls, the horseback rides through Painted Canyon, Bowman, the many mornings racing across the midwest. Yes, even within fissures of his past, love has existed, has grown, a rosebush flourishing in the midst of the Badlands. His puts out the embers, lays back, and allows his eyes to close.

…

The sun is a rising jewel. The morning is a fresh coat of paint being applied across the earth. There’s no better way to wake then by sunlight. Jack rises from a restful sleep and attempts to stoke the embers from the previous nights campfire, but to no avail. He slips on his boots, intent on gathering kindling. He pulls out a cigarette, strikes a match on his boot heel, lights up. It’s then that he sees the airship hovering at the precipice of his campsite. A huge, untethered, pristine white balloon, lit from beneath by a blue flame. He puts out the cigarette. An unknown compulsion draws him towards it. He hobbles his way into the white whicker basket and shuts the gate behind him. Without any effort, the balloon slowly ascends. Forgiveness is lighter than air. Before long the campsite is a speck. The entirety of the Dakotas is spread out below him, the land wrinkled and aging from years of human abuse. Yet the sky welcomes him. There’s no sound, save for the soothing roar of the blue flame.

–